Backlogs. Define and Implement Requirements Agilely.

What is a backlog? What sorts of backlogs are there? What advantages do they offer?

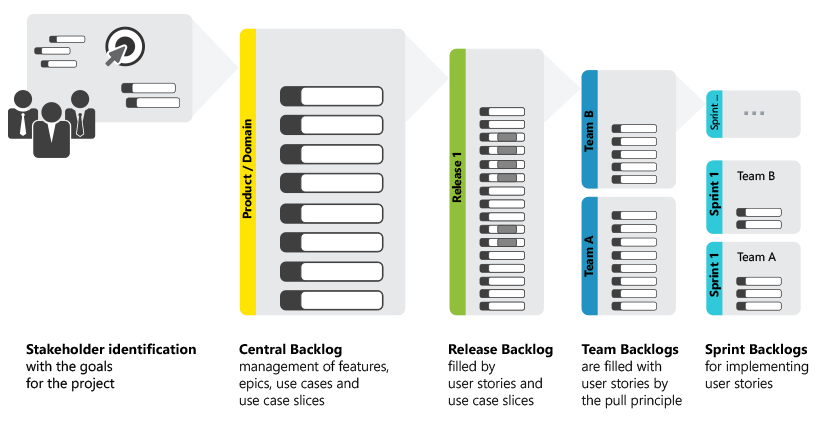

Big businesses often have large divisions - and the software development can be divided into different areas or domains, that have to implement different requirements. That's how domain backlogs emerge.

The order of the implementation of the requirements results from the prioritization with the appropriate allocation to the release backlogs.

If you work with multiple teams, you can distribute the requirements into team backlogs. This organization of the backlogs is leaned on the concept of the Scrum of Scrums. If you work with a single team, then only one backlog is necessary. Then the release backlog is also the team backlog.

A Backlog Is Not a Specifications Sheet

If you think about requirements and requirements management in software development, then you probably think about the specification sheets straight away – documents in which the features and functions required by the software manufacturer or contract provider are written down and then verified and removed. Full stop. But can’t the requirements of the software change during the development, so that the project team can adapt accordingly and be prioritized differently? Of course, for this reason agile project management methods have been developed in the past years and because of that they work with other aids. For example, in a Scrum project with backlogs.

Definition for backlog:

A backlog is initally a list of requirements

that the team has to process.

Product Backlog

he product backlog (sometimes called the domain backlog: normally when there is one backlog per domain) is the core of a Scrum project because it collects requirements that the software has to fulfil. That could be functions or bugs, for example, that the team should implement or fix. Normally so-called user stories are used in order to describe these requirements. That means, for example, that a new function from the view of the target group would be defined:

“As a visitor to this website, I would like to be able to use a search feature with which I can search the entire site and quickly find answers to my questions.”

Not all requirements are equally important or strenuous: they get a prioritization and an estimate of the effort they will take, and through these they are either implemented as soon as possible or put off until later. This task deals with the development team together with the so-called product owner, the representative of all the project’s stakeholder: whilst the priorities of the requirements are weighed up based on typical factors like the value of the business, the developers evaluate the effort of implementation. These estimates normally don’t produce absolutes, like ‘this requirement will take four person-days.’ Instead, they are given a relative value, like a Fibonacci number: a requirement with an effort of 2 is more quickly dealt with than one with a 5. At the end, there is a list in which the requirements are sorted according to their priorities.

If a project includes multiple teams, the tasks can be allocated to each team and then team backlogs can be created from them. If there is only one team, then the product backlog corresponds to the team backlog.

Release Backlog

A scrum project is divided into sprints and releases. For example, after three sprints comes the first release of the software. Afterwards, three more sprints follow and one more release. Requirements are automatically allocated according to their priorities to each release. So-called priority limits can be set for that: for example, there are for requirements with the priorities 100, 101, 102 and 102. For release 1.2, the product owner decides on a minimum value of 102. Because of that, only the priorities with the priorities 101 and 102 are launched in the release. If there are more requirements with priorities like 103 or 107, then they are also launched with release 1.2. Unless, of course, the next release 1.3 has a priority limit of 106, for example. In this way, so-called release backlogs emerge for each individual release.

Sprint Backlog

When the first product backlog has been created, the team allocates the requirements in the emerging sprints, so, the next iteration in the development. Which requirements should, for example, be implemented in the next two weeks? The team selects the user stories with the highest priority from the product backlog – so, requirements that are up the top of the list – whilst they also estimate what they can achieve in the time frame. If a user story is too broad, it is divided into smaller so-called tasks. In order to gain an overview of the current state of the implementation, task boards can be made use of – individual tasks are handled similarly to post-it notes, that can be stuck into columns of their states, like ‘to do’ and ‘done’. In professional software solutions, this step happens electronically.

Agile methods such as Scrum primarily distinguish between a product backlog, a release backlog and a sprint backlog.

Prioritizing – But What Is the Best Way?

Comprehensive projects create comprehensive backlogs – and it is not always clear which requirements are the most important or how they can be evaluated in comparison to others. That’s why there are methods that make prioritizing easier. For example, with the help of the Kano Model, features are classified as base factors, performance factors or enthusiasm factors. This classification is based on a survey of the users:

Are there features that a user expects in a certain context? Formatting options in a text editor, for example? Then this feature has a high base factor and has to be implemented. If it concerns an additional feature in order to expand the product, then the requirement has a high performance factor. If it’s just a small improvement, or decoration, then the feature can get the users enthused. This is how the developers and the product owner know which requirements they should prioritize in the current project context.

The MoSCoW principle is a similar process. Because it differentiates between, amongst other things, features that developers should definitely implement and ones that just could be implemented:

Must: must-have features that have to be implemented

Should: features to implement after the must-haves

Could: features that could be implemented if they don’t compromise the must-haves or should-have features

Won’t: features that won’t be implemented at the moment.

The backlog connects the development team with the product owner.

They can adapt the priorities of the requirements at any time

if the stakeholders want it.

The advantages summarized

So, the product owner together with the developers adapt the project backlog and with it the priorities in order to fulfil the wishes and circumstances of the stakeholders. They can also completely reject the requirements. This product backlog refining or grooming makes it possible to react quickly and flexibly to changes. At the same time, the developers already have a clear overview of the tasks that they have to process. This way, there is only one source of information and misunderstandings are reduced. Stakeholders also always know which requirements their team is working on at the moment – and every participant in the project can be sure that the most important tasks are currently being worked on. In summary, backlogs offer the following advantages:

- Backlogs create transparency about captured features, epics, use cases, use case slices and user stories.

- Backlogs structure the development of applications, products and software-intensive systems in terms of both content and time.

- Backlogs require regular, clear prioritisation and subsequently ensure high stakeholder acceptance.

- Backlogs are a very good working tool for the roles and staff involved.

- Backlogs are always up to date and show what is currently being worked on.